Economics of Migration and Migrant Remittances to Home country

The Comparative Analysis and the Bangladesh Story

Jamaluddin Ahmed FCA PhD

Is a Director of Emerging Credit Rating Limited, a former member of Board of Directors of Bangladesh Bank, former Chairman of Janata Bank, former President of the Institute of CA Bangladesh.

The aim of this paper was to determine which pillar of development, FDI or Remittances, contributes the most to economic growth in South Asia using data from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka between 1990 and 2012. We conducted our analysis through employing Random Effects GLS. The key finding was that FDI outperforms Remittances in enhancing economic growth in South Asia. In terms of our research questions, our first research question was validated; FDI positively contributes to economic growth in South Asia and that too significantly. However, our second and third research questions were not supported; Remittances do not positively impact economic growth and Remittances do not outperform FDI in enhancing economic growth in South Asia. With regards to our fourth research question: in which country does FDI or Remittances positively enhance economic growth the most. It is Sri Lanka.

Our findings about FDI in South Asia support many studies such as Tasneem and Aziz (2011), Balasubramanyam et al (1996) and Tiwari and Mutascu (2011). We can infer that an increase in FDI leads enhances economic growth and as such we suggest policies that open up the economy. For example, engage in more trade agreements, improve the quality of the infrastructure – both physical and political, and provide incentives for investors and so on. These policies could improve the attraction of FDI thereby enhancing economic growth.

Remittances impacted GDP negatively and this supports the studies of Barajas et al (2009), Russell (1986) and Catrinescu et al (2002). However, the remittance inflows are large in volume so governments should implement policies to increase financial literacy, establish easier but formal methods of remittance transfers, and provide savings’ incentives to migrant workers to further increase remittances transmitted through formal channels and promote growth. For Remittances to enhance economic development and growth, South Asia needs higher quality economic and political institutions.

For Bangladesh and Pakistan, FDI is crucial in enhancing economic growth. They should focus on policies to continue attracting more FDI such as engaging in more trade agreements and enhancing their infrastructure. However, in India and Sri Lanka, FDI did not positively contribute to GDP and this could be for a variety of reasons. They should improve their institutional framework and infrastructure to absorb more of the benefits from FDI. However, if they are over-dependent on FDI then they should focus on finding alternative sources of capital.

For Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, Remittances are pivotal in providing capital to achieve economic growth as well as poverty alleviation. Governments should make it easier for migrants to transfer remittances. For India and Pakistan, the significance of Remittances is inconclusive. However, this does not undermine their importance and they still need to improve many factors such as government policies and infrastructure since it is evident that Remittances are not being utilised in a manner conducive to maximum growth. Despite the importance of remittances, policy makers have not given them the attention they deserve. Policies for all these countries include providing incentives for migrants to save and invest their remittances, improving the access to financial services, educating residents about formal remittance channels and encouraging further market competition in the international remittance market to reduce costs.

Overall, we suggest that Bangladesh and Pakistan should focus on improving the necessary conditions to maximize the benefits from FDI since it positively impacts GDP. FDI and Remittances can provide the necessary tools to aid development and achieve higher growth levels through using its resources in the most efficient way. India and Sri Lanka need to enhance their human capital and improve: governance, physical and technical infrastructure and administrative capabilities to positively utilise FDI. However, India and Sri Lanka may be over-dependent on FDI and potentially should focus on improving the use of and attracting more Remittances, ODA and exports to finance their economic growth.

Future research could investigate the impact of FDI and Remittances on GDP in different sectors of the economy. It could also include more South Asian countries and perhaps split the countries according to their income levels and compare results. Other recommendations include comparing the impacts to other regions in the world and using interaction terms between FDI and Remittances and the various explanatory variables we included in this paper. This model itself could also be improved so as to include the omitted variables, Education Attainment and Life Expectancy, and examine their impact on GDP as well.

Theory of Migration and Review of Literature

Theoretical Studies, Neoclassical theories, structuralist views on migration, pluralist perspectives, theories of remittance, determinants of remittance, the age of remittance, migration and development debate, neo-classical equilibrium perspective, historical-structural theory and asymmetric growth, the push-pull framework, transitional models. Internal dynamics and feedbacks, social capital, network theory and chain migration, migration system theory, migration and development optimists vs. pessimists, dawning of a new era: developmental is views, migrant syndromes: cumulative causation and structural views, towards a pluralist perspective, new economics of labor migration, migration as a household livelihood strategy. Ongoing insights in to migration and development interactions, Migration and the propensity to invest in migrants sending areas. The indirect impact of migration on economic development, narrow and arbitrary definition of investment. Migration and inequality in a spatiotemporal perspective. Human capabilities, development and migration. Space, structure, migration and development etc are discussed.

Remittance corridors and the cost of remittance

A remittance corridor is typically between two countries where migration is common, such as between the United Kingdom and Somalia or between Norway and Poland (Carling, 2008, p.593). The World Bank (2015) reports the most common remittance corridors to the ASEAN countries. Review of empirical analyses of remittances are presented. A Brief History of Remittances in the United States dates back to Western Union’s introduction of its money transfer business in 1871. The Cost and Accessibility of Remittances Originating from the United States with a focus on the Mexico Corridor). The cost and benefits of immigration, immigration pathways, economic costs and benefits, hi-tech development, social costs and benefits in the united states are explained. The central question for immigration policy is the balance between costs and benefits. Vivek Wadhwa and colleagues reach a clear conclusion based on their studies. They say that “immigrants have become a significant driving force in the creation of new businesses and intellectual property in the U.S.—and that their contributions have increased over the past decade.” In contrast to critics who worry that immigrants take American jobs and depress American wages, considerable research suggests that immigrants contribute to the vibrancy of American economic development and the richness of its cultural life. They start new businesses, patent novel ideas, and create jobs. When one strips away the emotion and looks at the facts, the benefits of new arrivals to American innovation and entrepreneurship are abundant and easy to see. The costs immigrants impose are not zero, but those side-effects pale in comparison to the contributions arising from the immigrant brain gain.

Economics of International Migration and Technological Progress

International migrants are an important channel for the transmission of technology and knowledge. The so-called “brain drain” associated with better educated citizens of developing countries working in high-income countries is acute in some developing countries. Emigration rates of the university-educated tend to be higher than for the general population in developing countries. This is even greater for scientists, engineers, and members of the medical profession. For some countries, the brain drain represents a significant problem: emigration rates of highly educated individuals exceed 60 percent in some small countries. In addition, the emigration of professionals who make a direct contribution to production, such as engineers, may result in reduced rates of domestic innovation and technology adoption. In countries with more moderate out-migration rates, the creation of a vibrant and technologically sophisticated diaspora may be beneficial in net terms, especially when domestic opportunities are limited, because of technological transfers from the diaspora and because most migration is not a one-way flow. The diaspora as a brain bank. Diaspora networks and returnees help promote technology adoption, remittances can promote technology diffusion by making investments more affordable. What influences remittance cost are underdeveloped financial infrastructure, limited competition, and lack of transparency in the financial market, regulatory obstacles, lack of access to the banking sector by remittance senders and/or recipients, lack of digital and financial literacy skills, lack of trust in the financial system and lack of access to necessary identification documentation for migrants are some of the main reasons for high remittance costs which influences remittance cost. Remittance cost architecture and transparency, market arrangements, digitalization of remittance services, users’ behaviour, driving a price revolution, assessing the impact of mobile money on lowering remittance prices and costs are discussed.

Barriers to remittance markets: A Comparative Analysis of Sub Sharan Africa

Barriers to remittances, commercial/Business case barriers, middle-mile barriers, infrastructure, consumer and regulatory, ranking barriers and fast payment systems in selected countries are explained. The remittance market in Africa is on average the most expensive in the world. Sending and receiving funds in the region is not only costly in terms of price for the consumer but also in terms of access of remittance service points. Especially the rural population often has to travel long distances or spend an entire day in a queue to pick up over-the-counter remittances. To reduce the cost to the consumer, the cost of doing business over the entire remittances value chain needs to be reduced while ensuring improved access at the first and last mile for consumers. The remittance value chain requires a fine balance between cost, price and access from a consumer perspective. Merely reducing a price does not mean that the effective cost or level of access to a consumer remains static.

The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benefits of innovation and competition

Remittances are born of sacrifice and separation. Remittances are monetary lifelines sent by migrant workers back home. Remittance inflows are critical—and they have been resilient in challenging times. Remittances are key to many Lower Middle-Income Countries. Digital remittances were key to the resilience of inflows, but we need to enable more of them. The Price of Remittance: Do high transaction cost depress Transfer. Global Consensus to Reduce Remittance Costs. Costs and Methods of Sending Remittances. Trends in Remittances & Cost Reductions. Overview of Efforts to Reduce Remittance Costs and literature on cost of migrant remittance are discussed. An analysis of the impact of cost on amount remitted are presented. Two recent studies on the impact of mobile money in Bangladesh and Ghana also provide evidence of the potential impact of reducing the cost of person-to-person money transfers. In a randomized controlled trial facilitating mobile-money access and providing training on how to use it in Bangladesh, Lee et al. (2018) find that access to mobile-money services led, approximately, to a 30% increase in urban-to-rural internal remittances. Cost measurements include transfer charges and foreign exchange margins are explained. Cost modelling confirms the value of digital remittances and the ability to compare options are detailed. Used publicly available tools to model costs have been analysed. Comparative remittance fees to the Philippines are among the Lowest in East Asia and Pacific. Average Costs of Sending $200 (%) to a Particular Region of the World.

Reasons for high remittance costs are presented. Structural transformation, urbanization, and remittances in developing countries. Traditional remittances must become digital to continue lowering costs reasons justified. How we unlock the benefits of remittance innovation and competition for everyone, everywhere are explained.

Migrant Remittances and Economic Complexity

Policymakers and researchers are keen on identifying the potential benefits of these inflows in promoting economic development. This section let us first look at the economic impacts of foreign remittances. Foreign remittances are important in increasing foreign exchange reserves in developing countries. Migrant remittances are more stable in nature in comparison with other capital inflows. Remittances and Economic Growth effects of remittances on growth have been discussed extensively in the literature on remittance and growth. Remittances are primarily used for consumption, accumulation of assets, and productive investment at the household level. Combined Effects of Remittances and FDI. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework have been analysed. Migrant remittances are also used for productive investment, which boosts economic development in developing countries. Remittances also help bring and adapt cutting-edge technologies, bringing innovation to the industries in the recipient economies. There are several ways through which remittances influence recipient countries’ economic growth. Remittances enhance aggregate consumption and bring productive investment by raising the saving capacity of the remittance-receiving households resultantly, all these factors lead to cause economic growth. Remittances stimulate investment and help in reducing credit constraints in the absence of formal credit markets in low-income countries. There are several other potential channels through which remittances may directly or indirectly impact economic growth. remittances can be used as an investment to enhance economic capital accumulation. Remittances sent through the formal banking system is another channel that helps increase the aggregate amount of deposit that might affect the economy and ultimately lead to capital accumulation. Remittances are, currently, the second most important source of external finance to developing countries, after foreign direct investment. Remittances tend to be more stable than volatile capital flows such as portfolio investment and international bank credit. Remittances are also an international redistribution from low-income migrants to their families in the home country. Microeconomic motivations to remittance has a positive role. Stability of remittances in the economic cycle and workers remittances are more stable than portfolio investments and bank credit. The development impact of remittances have been analysed. Remittances may also have a poverty reducing and income distribution effect. The international markets for remittances are discussed. Cost of remittance have been elaborated. Country experience have been explored. Theoretical justifications of remittance are placed.

Impact of Remittance on Economic Growth of Bangladesh

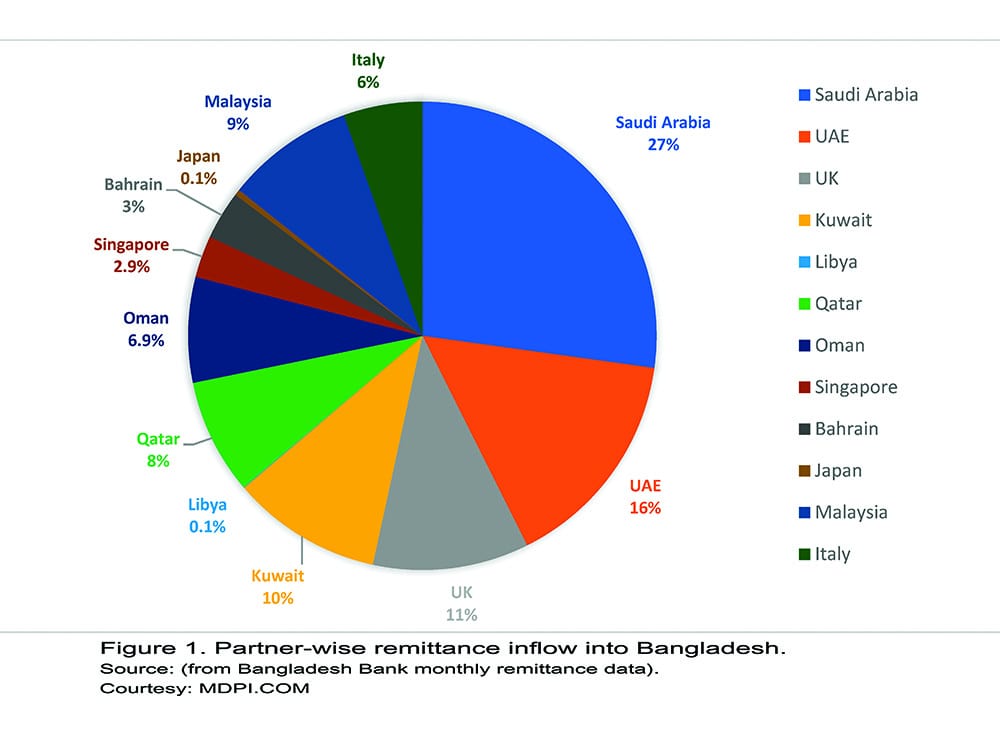

Most Bangladeshi emigrants are men, although more women have been leaving, particularly to go to the Middle East and East Asia. However, they do not always secure a stable income or safe residence; many have been victims of torture and violence, including sexual exploitation, and have returned to Bangladesh. Millions have taken short-term contracts abroad, with a record 1.3 million leaving in 2023 alone. In addition, an unknown but large number of Bangladeshis have taken unofficial overseas contracts that are not registered with the government. The nature of labor migration from Bangladesh is mainly short-term, based on unskilled or semi-skilled work. More than 7.4 million Bangladesh-born individuals lived abroad as of 2020, according to UN estimates. The money these migrants and others send back—$21.9 billion via official remittance channels in 2023, according to the government—is a major source of development for Bangladesh. Aside from India, Saudi Arabia has long ranked as the largest origin of official remittances to Bangladesh, accounting for $4.1 billion in 2022, followed by other Gulf countries. Most Bangladeshi emigrants are men, although more women have been leaving, particularly to go to the Middle East and East Asia. However, they do not always secure a stable income or safe residence; many have been victims of torture and violence, including sexual exploitation, and have returned to Bangladesh. The territory that was once a part of the British colony of India and after the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 became known as East Pakistan was recognized as an independent country on December 16, 1971. The migration history of what is now the People’s Republic of Bangladesh is divided into five important phases.

In the precolonial era, there is ample historical evidence that the region once known as East Bengal experienced frequent international and internal migration, which helped make it famous for tea cultivation. In a second phase, during the British colonial period (1858-1947), many people especially from Bangladesh’s northeastern Sylhet district moved to England and worked in British shipyards and other sectors. A third phase occurred amid the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. As many as 20 million people moved between and within both countries, with religion often a motivating factor; many Muslim people left India and settled in Pakistan, while Hindus went in the opposite direction.

The nine-month 1971 war of independence triggered Bangladesh’s fourth phase of migration, with approximately 10 million people displaced from Bangladesh across the Indian border, many of whom—particularly Hindus—did not return afterwards. Moreover, many people living in Pakistan since 1971 have been unable to return to their native Bangladesh, while people in Bangladesh with Pakistani roots, called Biharis, have sought to be repatriated to Pakistan. The current and fifth phase began after independence. Bangladesh’s fragile economy had limited job opportunities, resulting in large numbers of semi-skilled and unskilled male workers moving temporarily for employment in the Middle East, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Many of these patterns began in 1973, when oil prices rose and several Gulf countries had a rapid demand for new infrastructure. The heterodox migration process continues to this day, even as the world’s eighth most populous country has been touted as a model of development and an economic miracle, in part because of the reliance on exports as a driver of domestic growth.

Although most Bangladeshi migrants work in low-or semi-skilled sectors abroad, they are driven in part by a mismatch between Bangladesh’s educational offerings and job prospects. As a result of a massive increase in educational institutions in Bangladesh, the number of educated people has risen, including in rural areas, yet there are not sufficient employment opportunities for them. Much of the economy relies on agriculture and the booming garment sector. And due to factors such as economic insecurity, depressed wages, and the absence of a robust social safety net, there is a growing interest among the educated population in emigrating rather than local entrepreneurship. Environmental vulnerability also contributes to the drivers of migration, especially when combined with poverty and poor labor market conditions, providing a strong impetus for seeking work abroad.

The vast amount of money sent back by emigrants and others as remittances has been among the most powerful tools in Bangladesh’s economic outlook, contributing to improving the living standards of families and spurring development. Although the country’s domestic garment sector is said to be the highest foreign income earner, accounting for nearly $47 billion in 2023 (more than 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), remittances are likely more important. This is because a significant amount of garment export earnings covers the cost of importing raw materials, thereby reducing net income. Therefore, official remittances, which added up to nearly $21.9 billion in 2023, are likely the top income-generating economic sector for Bangladesh. International remittance flows have generally risen swiftly since Bangladesh’s independence, increasing from $1 billion in 1993 to $12.8 billion in 2013 and $18.4 billion in 2019 (see Figure 3). During the COVID-19 outbreak, fewer Bangladeshi workers were able to travel overseas and many analysts predicted remittances would decline significantly in Bangladesh and other major remittance-receiving countries. However, recorded remittance transfers to Bangladesh remained resilient, and rose to $21.8 billion in 2020—a 19 percent increase over the previous year.

Bangladesh is the sixth largest migrant-sending country globally, and the eighth largest remittance-receiving country, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). According to Bangladesh government statistics, workers have taken nearly 16.1 million short-term labor contracts in 164 countries around the world from 1976 through 2023, with the overwhelming majority in the Persian Gulf. Some may have returned to Bangladesh after their contract ended; others were forced to return for a variety of reasons, such as unsuccessful health tests or poor job performance. Moreover, some migrants die while abroad—including more than 1,000 Bangladeshis who reportedly died in Qatar during the decade-long build-up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. And many return after their contract ends.

Of the more than 7.4 million Bangladeshi migrants abroad as of 2020, approximately 1.3 million were in Saudi Arabia, 1.1 million in the United Arab Emirates, and 380,000 in Kuwait, with smaller numbers elsewhere in the region, according to UN statistics. Migration has been increasing to other Asian countries such as Malaysia (home to 416,000 Bangladeshis as of 2020), Singapore (80,000), and South Korea (12,000). Nearly 2.5 million Bangladeshis are believed to live in neighboring India, many likely without authorization. Irregular migration between the two countries is a controversial topic given their history. During the COVID-19 outbreak, fewer Bangladeshi workers were able to travel overseas and many analysts predicted remittances would decline significantly in Bangladesh and other major remittance-receiving countries. However, recorded remittance transfers to Bangladesh remained resilient, and rose to $21.8 billion in 2020—a 19 percent increase over the previous year.

Remittance inflows through formal channels have remained relatively stagnant since 2020. The World Bank predicts that remittances to South Asian countries in general will slow down somewhat in 2024, although the region is projected to receive the most remittances among those sent to low- and middle-income countries. India, Bangladesh’s neighbor, is the world’s largest remittance recipient (with an estimated $125 billion in remittances via formal channels in 2023) and Pakistan is also a major remittance receiver ($24 billion in 2023). However, it is impossible to calculate precisely how much money comes to Bangladesh and other countries via all forms of remittances, due to the large sums believed to travel through unofficial channels. Because of currency devaluation and exchange rate management policies, among other factors, many people sending money to Bangladesh do so through informal channels such as the hawala system or via gifts and goods that migrants bring with them on their return.

Remittance-receiving households in Bangladesh tend to be better off financially and socially than others. Families often spend remittances on consumer goods such as food, clothing, education, medical care, and shelter, and this is especially true for poor urban and rural households. This income thereby improves households’ standards of living. Moreover, remittance-receiving households may use a significant portion of the inflows to purchase land and (for agricultural households) improve farming techniques such as by making investments in modern machinery. Because Bangladesh is incredibly vulnerable to natural disasters, remittances place recipient households in a stronger position to bear future risks. This in turn enables private savings, diversified livelihoods, and investment in small businesses. Remittance-prompted investments in land, agriculture, and housing also boost local markets and stimulate rural economies. These transformations can increase mechanization of agriculture, cash crops, and fisheries, directly contributing to local community development. Remittances can make it easier for receiving households to become self-employed in these sectors and to hire other workers. When households use remittances to construct, expand, or improve their homes, they increase the demand for labor and raw materials, thereby contributing significantly to local employment. Remittance senders also tend to contribute to the public life of their communities of origin by making donations to local schools, colleges, libraries, religious institutions, and other facilities.

Negative Impacts of Migration and Remittances

For the time being, emigration of Bangladeshi laborers does not have significant negative consequences for the country. However, there can be risks to individuals (and their families) who bear the predeparture costs of migration—which are often excessive—meaning migrants must spend time abroad to recoup their money, and workers who cannot complete their contracts may lose sizable sums. Over the long term, Bangladesh’s dependence on remittances may pose future risks, increasing the need to diversify the country’s fiscal situation. Otherwise, the economy may become vulnerable to headwinds outside of its control. While remittances sent via formal channels did not drop as expected during the pandemic, transfers could still be affected by future events. A potential decline in remittances requires innovative policies that reduce the country’s dependence and increase domestic sources of revenue. Since most remittances come from unskilled and semi-skilled laborers, a skilled workforce and new labor markets could lead to employment for different occupations and more resilience to remittance-related challenges.

Migration Governance

Bangladesh’s migration governance is multidimensional. The country has made significant progress in priorities such as ensuring the well-being of migrants, protecting their rights, and responding to crises, although there remain some critical problems. For instance, the national framework has focused on labor migration at the expense of other forms of cross-border human mobility, such as humanitarian migration, which may have complicated the government’s efforts to respond to the population of Rohingya refugees. Bangladesh has no law specifically governing refugee and asylum issues, and the government has maintained that the Rohingya population is only temporary.

Role of Remittance in the Economic Development of Bangladesh

Increased economic activities due to economic globalization in the 1980s and 1990s led to a rapid international rise in demand for skilled and unskilled manpower. That paved the way for many people, including those of the developing countries, to move to the outside destinations (Castles & Davidson, 2000). For a large number of Bangladeshi workers, mostly semiskilled and unskilled, this external demand opened up opportunities for earning their livelihood abroad. Many others have also left the country for different pull and push factors. This migration was, however, a welcome relief for Bangladesh as its development strategies since independence could not cope with and accommodate the growing demand for employment from a fast growing population. The consequence of the multidirectional relocation of people, both temporary and permanent, was the quick rise in remittances in the economy of Bangladesh.

As a parallel development to this growth in outward movements of workforce, the volume of inward remittances has accelerated to become a regular and substantial source of resource transfer in the Bangladesh economy, although this was not the case until 2000 when remittances were seen as trivial in size and had little developmental relevance. In fact, remittances now stand many folds to its foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance (ODA) combined. According to the MRF 2011, official remittances to Bangladesh exceeded US$11 billion in 2010, making it the eighth largest remittances recipient country in the world (World Bank, 2010, p. 58). Certainly, this was a significant flow of fund for Bangladesh. Indeed, a regular growth in the flow of remittances has upended the developmental significance of remittances, both in social and economic sectors, in the eyes of the policy strategists.

The development impacts of remittances may be assessed by the effects remittances have on various short- and long- term micro and macro socioeconomic variables. Again, these impacts are considered to be more in the developing countries with higher poverty incidence and lower financial development density (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, 2009; Jongwanich, 2007). The remitters, who were mostly unemployed in their home countries, have now jobs in overseas places. This may create limited employment opportunities for the others in the home country. Likewise, the remittances they are sending back may help employment generation domestically as well. The latter happens through the reinforcement of remittances-induced national savings, capital accumulation, and investment (Barua et al., 2007). So the direct, trickle down, and indirect benefits of remittances could be significant in aggregate for many of the developing countries.

Uses of Remittances and Impacts on Socioeconomic Factors in Bangladesh

In analyzing the transfer and utilization dynamics of remittances, De Bruyn and Kuddus (2005) find that remittances inflows in Bangladesh happen mostly in the forms of (a) transfer to family and friends and (b) transfer to save or invest, and not much in the forms of (c) transfer to charity or community development and (d) collective transfer to charity or community development. So the impact assessment mainly centers on the first two types of transfers. Sensibly, in those two types of transfers, the recipients are often the father, mother, spouse, other family members or even relatives of near and far.

Beyond Economics: Practice of Family Culture of Bangladeshi Migrant from Los Angeles USA

Hasan Mahmud (2021) conducted a study Beyond Economics: the Family, Belonging and Remittances among the Bangladeshi Migrants in Los Angeles. Based on migrants’ perception, the paper recognizes the centrality of the family and origin community in migrants’ remittances both in the NELM and in the transnational perspectives. It empirically investigates migrants’ belonging and recognizes their membership in their parents’ family, their own nuclear family, joint family including siblings with their respective families, extended family including multiple generations and a community of origin. It finds migrants’ belonging simultaneously to the destination and origin countries, and also confirms the presence of ‘friction’ in such belonging, indicative of both cooperation and conflict in migrants’ remittances allowing for explaining changes in their remittances such as remittances decay and resurgence. This study offers guideline for further empirical research on migrants’ transnationalism and remittances with policy implications regarding the developmental consequences of remittances.

Migrants’ belonging to home and remittance

Remittance is defined as the money migrants send home to their origin country. Scholars recognize the family as the primary recipient of a migrant’s remittances as acknowledged in the United Nations’ declaration of 16 June as the Family Remittance Day. Studies on transnational families and remittances demonstrate that migrants send remittances from a sense of responsibility and obligation to help the family (Abrego, 2014; Mahmud, 2014; 2020; Parreñas, 2001; 2010; Thai, 2014; Vanwey, 2004; Wong, 2006). The concept of ‘home’, central to understanding migrants’ belonging to the family and remittances, is often used interchangeably with the household or the family. The household–according to the NELM approach–is a social unit consisting of parents, spouse and children with share economic interests and something that migrants leave behind in their origin country. In comparison, the family – as obvious in the transnationalism approach – is a union of intimate relations that the migrants maintain across borders and reunite with when and where they can. Thus, migrants’ home is both ‘a private domestic space and a larger geographic place where one belongs, such as one’s community, village, city, and country’ (Espiritu, 2003, p.2). Terms like ‘homeland’ and ‘hometown’ also reveal the spatiality of migrants’ conception of homes (Castaneda, 2018). However, home in this sense is not a place one comes from but a habitation. As Wise (2000, p.299) demonstrates, home as a place/territory does not exist ‘out there’ but is an act, a process of territorialization, a conscious effort to conquer a space as one’s own. Home is an experience that evokes–as Boccagni (2017) argues–security, familiarity and control. Home is where the individual finds expressions of being and becoming among a set of relations in a certain space (Boccagni, 2017; Castaneda, 2018; Wise, 2000).

Beyond the economics of remittances

The NELM perspective assumes sending remittance is a reciprocation in the part of the migrants towards their family (i.e. self-interested remittance), while it is actually a conforming behaviour towards a distinct cultural norm. In Bangladesh, the sons are expected to share responsibility for their family once they grow up and begin to earn (Ballard, 1982; Indra & Buchignani, 1997; Kabir et al., 2002). When Bangladeshis migrate to various countries abroad, they bring this culture of sharing family responsibility with them. Thus, Mobin (24 years in the United States, living with wife and a child) told us: Ninety eight percent [that is, nearly all] Bangladeshis earn and send money to their families. This is because they come from financially struggling families. They grew up in poverty. They want to help their family to have a better life. HM: Do they consider their self-interest in this remitting. Mobin: No, it is our responsibility. We think that we come to America and earn money. So, we will send money. There is no other consideration. This sense comes from one’s inside. This is because we are brought up in this way, this is our culture, nothing else.

Sense of belonging, familiy Dynamic and changing remittances

Migrants’ sense of their responsibilities and obligation to the origin family is indicative of the presence of what Thompson (1971) calls moral economy: local social and cultural conceptions of who ‘ought’ to receive migrants’ remittances. Thus, a satisfactory understanding of the topic requires examining how this moral economy functions within the dynamic family structures and transnational relations (Abrego, 2014; Boccagni, 2013; Carling, 2008a; Contreras & Griffith, 2012; Silver, et al., 2018; Thai, 2012, 2014). Scholars recognize gender, generation, migrant’s position within the household and the question of return or permanent settlement as decisive factors in shaping migrants’ remittances (Carling, 2008b), but also see the migrants as embodying culturally specific roles within the family and origin community. This membership or belonging to the family and origin community–a social fact in the Durkheimian sense (Durkheim, 1982)–shapes migrants’ remittances.

Diaspora Contributions to Development in Their Countries of Origin

For many diasporans, the experiences and opportunities they are exposed to in their countries- of residence inspire them to seek ways to contribute to the development of their countries-of-origin. They engage with their countries of-origin in many different ways, including (1) advocacy and philanthropy; (2) remittances, investment, and entrepreneurship; and (3) tourism and volunteerism. Some diasporans join diaspora advocacy groups, lobbying the government of their country-of-residence on behalf of development issues in their countries-of-origin. Other diasporans strive to enhance the development of their countries-of-origin by engaging in philanthropic activities, raising money in the country of residence or volunteering their time for social and environmental organizations located in the country-of-origin.

People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Taka Denominated Diaspora Bond

Bangladeshi diasporas can invest any amount up to BDT 01 (One) crore converted against foreign remittance 05 (Five) years are allowed to invest complying the documentary requirements and applying simple interest rate.

Special Benefits; Bangladesh: The U.S. Dollar Premium Bond Rules, 2002; Additional Benefit for Substantial Investment; Additional Benefit for Substantial Investment The Wage-Earner Development Bond Rules, 1981 and Additional Benefits for Substantial Investment.

Extending Digital MFS Services at Remittance Corridors Currency Diaspora Bonds

Government of Bangladesh may form a committee to work out a plan to collect more migrant remittance by selecting 10 best performing commercial banks allowing them to issuing diaspora bond through formulating a standard operating procedures by forming a committee comprising of representative from the Finance Ministry, Foreign Ministry officials from different remittance corridors, MFS experts, BAIRA officials, Central Bank, Bankers Association, Economists, Lawyers with Banking experience and any other of government choice.

Expand MFS activities to significant remittance corridors to collect diaspora remittance Digitally MFS companies in collaboration with Central Bank of Bangladesh should plan establishing their branch office in remittance corridors to extend MFS activities which many countries are following can be a example for Bangladesh.