Ethnic Identity and National Security: Rethinking the Chittagong Hill Tracts

Major General (Retd) Dr. Md. Nayeem Ashfaque Chowdhury

Chief Executive Officer, Prime Bank Foundation.

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) remain one of Bangladesh’s most geopolitically sensitive and culturally complex regions. As the nation continues to uphold its constitutional values of equality and sovereignty, it is imperative to revisit the evolving discourse surrounding ethnic identity, indigenous claims, and national security.

Who qualifies as indigenous in Bangladesh? Do such communities exist within the historical and legal framework of our state? What are the implications of recognizing certain ethnic minorities as indigenous, and how do these claims align—or conflict—with our Constitution?

Articles 27, 28(1), 28(2), and 29(1) of the Constitution of Bangladesh guarantee equal rights to all lawful citizens, regardless of ethnicity, origin, or faith. Yet, questions persist: Are we doing enough to ensure these rights for all communities, especially those residing in the CHT? Are external narratives and international conventions shaping domestic policy in ways that challenge our national cohesion?

This article explores the historical migration patterns of ethnic groups in the CHT, the legal definitions of “indigenous” under international law, and the constitutional safeguards that govern our national identity. It also examines the socioeconomic disparities and emerging security threats that demand urgent and unified attention.

Historical Context: Migration, Settlement, and Identity

The land that is now Bangladesh has long been a cradle of civilization, where Bengalis and various ethnic groups have coexisted for millennia. Archaeological discoveries across the country attest to continuous habitation and cultural development dating back thousands of years. Evidence of Buddhist civilization from the 3rd century BCE has been found in Mainamati (Cumilla), while ancient Pundranagar and Maurya-Gupta relics have surfaced in Mahasthangarh (Bogra). River-based settlements in Chandradwip (Barisal), and prehistoric pottery and tools in Rampura and Uralbari (Dinajpur), further affirm the region’s deep historical roots. Excavations in Wari-Bateshwar (Narsingdi) reveal urban activity dating from 400 to 100 BCE. These findings, along with the legacy of the Pal and Sen dynasties, Mughal rule, and British colonialism, confirm Bengali presence in the region since prehistoric times.

Bangladesh is currently home to 45 ethnic minority groups, 13 of which reside in the CHT. Historical records and ethnographic research indicate that these communities migrated from neighboring regions—India, China, Myanmar, and Tibet—over the past several centuries. Their settlement in the CHT was shaped by political upheaval at their ancestral place, displacement, and economic necessity. For example:

Chakma: According to research compiled by Mongol Kumar Chakma, James Ward

Khokshi, Pallab Chakma, Mongsingkre Marma, and Helena Babli Talang in

Bangladesher Adibashi, the Chakma people originated from Champaknagar in Myanmar and migrated to the CHT less than 500 years ago. A Portuguese map from around 1550 by cartographer Lavanha references the Chakmas, suggesting their relatively recent arrival.

Marma: As documented in Banglapedia, the term “Marma” derives from the Burmese word Mranma, meaning “inhabitant of Burma.” The 1788 Buddhist chronicle Dhanyavati Ayedoban identifies them as Mranma. Following the annexation of Arakan by Burmese

King Bodawpaya in 1784, the Marma people were displaced and sought refuge in the CHT. During British rule, they were pejoratively labeled “Mog,” a term associated with piracy. In the 1940s, the community formally adopted the name “Marma” to reclaim their identity.

Ethnic minority groups of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT)

Tripura: The Tripura ethnic group originally hailed from the Indian state of Tripura. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, they migrated to the CHT due to political instability, population pressures, and agricultural needs. They speak Kokborok, a language belonging to the Tibeto-Burman family.

Kuki Ethnic Group: The Kuki ethnic group, comprising subgroups such as the Lusai,

Bom, Pangkhua, Mro, Khyang, and Khumi, is believed to have migrated to the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) between the 15th and 18th centuries. Their origins trace back to Myanmar’s Rakhine and Chin states, as well as India’s Tripura and Mizoram regions.

Linguistic, anthropological, and ethnographic studies confirm that all ethnic communities currently residing in the CHT settled in the region as migrants. This conclusion is supported by the works of renowned scholars including R.H.S. Hutchinson (1906), T.H.

Lewin (1869), Amarendra Lal Khisa (1996), J. Jaffa (1989), and N. Ahmed (1959). These findings challenge the narrative that any of these groups are indigenous to the region in the prehistoric or colonial sense.These migration narratives underscore a critical point: while these communities have long contributed to the cultural mosaic of Bangladesh, their arrival in the CHT occurred well after the region’s earliest settlements. Understanding this historical context is essential when evaluating contemporary claims of indigenous status and their implications for national policy.

Legal Context: Indigenous vs. Tribal Recognition

The international discourse on indigenous rights is shaped primarily by two conventions and one declaration under the United Nations framework. The first, ILO Convention 107 (Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention, 1957), was adopted to improve the welfare of tribal and semi-tribal populations not fully integrated into national societies. Bangladesh ratified this convention on June 22, 1972—prior to drafting its own constitution—thereby recognizing the distinct identity and cultural heritage of its tribal communities.

However, Article 1(b) of the convention defines tribal peoples as descendants of those who inhabited a region prior to colonization or conquest, maintaining distinct social and cultural characteristics. Given that Bengalis have lived in the region for over a millennium before British rule, the tribal communities in the CHT do not meet this definition. This raises the question of whether Bangladesh should reconsider its continued ratification of Convention 107.

In response to global criticism, the ILO revised the framework and introduced

Convention 169 in 1989. This newer convention merges tribal and indigenous identities and allows communities to self-identify as indigenous. It also recognizes rights to self-governance and land ownership. Due to its controversial provisions, only 24 countries ratified it—Nepal being the sole Asian signatory. Bangladesh, asserting that it has no indigenous peoples, did not ratify this convention.

In 2007, the UN adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which exclusively addresses indigenous populations. Bangladesh abstained from voting, maintaining its position that no such communities exist within its borders. UNDRIP grants indigenous peoples political, economic, and social autonomy, and permits UN intervention in member states to protect these rights. Concerns over sovereignty, land laws, and constitutional conflicts led several countries—including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada—to oppose the declaration.

Following UNDRIP’s adoption, certain interest groups in Bangladesh began lobbying under the banner of cultural activism to push for political autonomy. Reports were submitted to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), prompting the Government of Bangladesh to reiterate—most recently in 2022—that no indigenous peoples exist in the country.

Clause 52 of the CHT Regulation 1900 identifies tribal communities in the region as migrants. The Constitution, CHT Peace Accord, District Council Act, and Regional Council Act consistently refer to them as “tribal.” On September 9, 2008, the Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts formally informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Bangladesh has no indigenous peoples. At the time, Barrister Debashish Roy served as Special Assistant to the Ministry.

Bangladesh Army on patrol in the hilly region.

Public statements by tribal leaders further affirm this position. On December 27, 1992, Santu Larma declared at a press conference in Dudukchhara, Panchhari, “We are not tribal, we are a small nation.” In 1972, his brother Manabendra Narayan Larma stated in Parliament, “I am not Bengali, I am Chakma, a tribal from the Chittagong Hill Tracts.” In a 2011 interview with Channel i, Bomang King Aung Shaw Prue of Bandarban stated unequivocally, “We are not indigenous, not even tribal.”

India’s constitution does not officially recognize any group as indigenous. Instead, it categorizes communities as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Ethnic groups such as the Chakma, Marma, and Tripura reside in India but have never claimed indigenous status. In Arunachal Pradesh, the Chakma community seeks recognition as Scheduled Tribes—a demand that faces local resistance.

Socioeconomic Context: Uneven Progress and Lingering Disparities

The Constitution of Bangladesh enshrines equal rights for all citizens, regardless of ethnicity or origin. Article 23A, introduced through the Fifteenth Amendment in 2011, mandates the State to “preserve, develop, and promote the distinct culture, heritage, and legacy of tribes, minor races, ethnic sects, and communities.” This constitutional provision reflects a commitment to inclusive development and cultural preservation.

Yet, in practice, equitable socioeconomic progress across the CHT remains elusive. Despite decades of investment, disparities persist among the region’s 14 ethnic communities—including the Bengali population. For instance, the literacy rate among the Chakma community stands at 76%, while it is only 23% among Bengalis residing in the CHT. The average literacy rate among tribal groups is approximately 44%, highlighting uneven access to education and opportunity.

Historical accounts, such as those found in a memoir on Manabendra Narayan Larma, reveal that tribal society in the CHT was traditionally divided into two classes: the upper class, comprising royal families and officials, and the lower class. The period from 1971 to 1997 marked the emergence of a tribal middle class, as individuals began entering government and private employment. From 1997 onward, this middle class has seen significant expansion. The memoir acknowledges the socioeconomic progress of tribal communities since independence.

However, this progress has not been uniform. The recent Kuki-Chin insurgency underscores the consequences of uneven development and perceived marginalization.

Allegations of discrimination persist in international NGO projects operating in the region, and concerns have been raised about bias in the selection of tribal students for foreign scholarships.

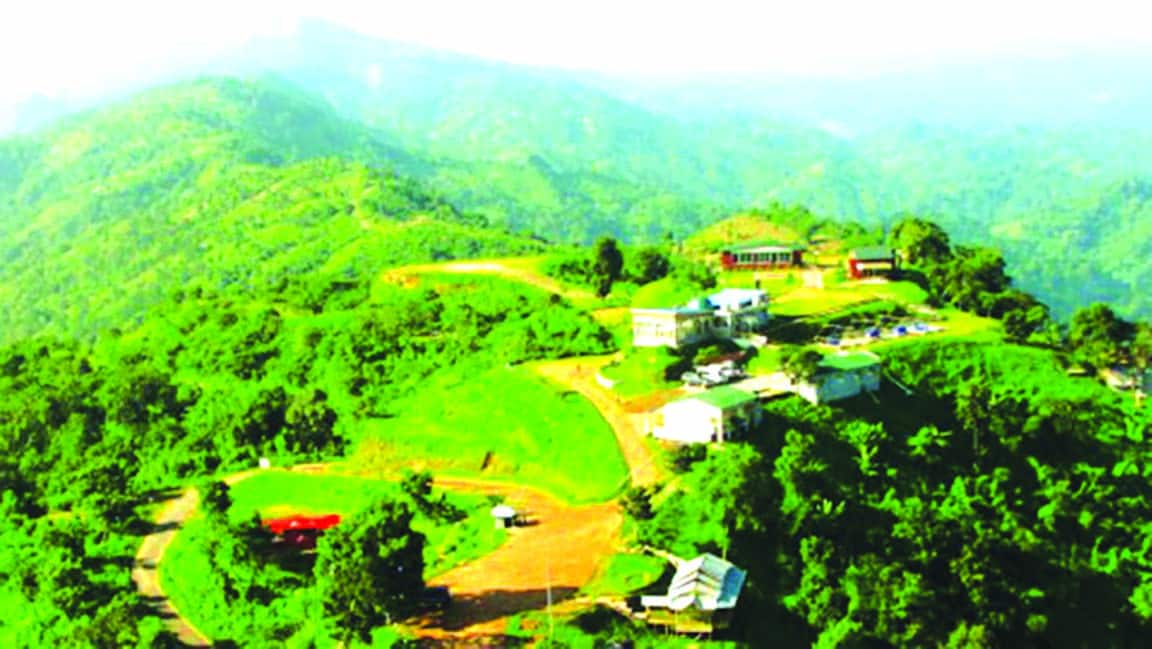

Nonetheless, it is undeniable that the CHT has witnessed substantial development since independence. Infrastructure projects have brought roads, schools, colleges, universities, and medical facilities to the region. Tourism centers and modern agricultural practices have also contributed to economic growth. Yet, despite these advancements, the echoes of armed conflict continue to reverberate through the hills—reminding us that development alone cannot resolve deep-rooted grievances.

A more inclusive and balanced approach is needed—one that ensures all communities, tribal and Bengali alike, benefit equitably from the nation’s progress.

Despite the government’s highest efforts, the sound of weapons still echoes in the hills today.

Security Context: Strategic Vulnerabilities and the Urgency of National Cohesion

The CHT occupies a critical position in Bangladesh’s geopolitical landscape. As regional power dynamics shift—particularly with the growing contest between the Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—the strategic relevance of the CHT is likely to intensify. Shared ethnic ties across Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar have already facilitated cross-border trafficking of arms, ammunition, and narcotics, posing serious threats to national security.

Reports indicate that certain ethnic groups in the CHT maintain links with armed factions in India’s Manipur and Mizoram. Historical evidence confirms that India provided shelter, training, and logistical support to the Shanti Bahini. Even today, India remains a primary source of arms and refuge for groups such as the JSS and UPDF. Prior to the signing of the Peace Accord, only one insurgent group operated in the hills; now, six such factions are active.

The Peace Accord led to the withdrawal of 241 security camps, creating a vacuum that has since been exploited by regional political parties and their armed wings. This has resulted in a surge in extortion, abduction, and armed conflict. Bangladesh shares a 271 km border with Myanmar, of which approximately 144 km remains unfenced. Similarly, the CHT shares a 496 km border with India, with around 135 km lacking physical barriers. These porous borders have enabled the unchecked movement of weapons, narcotics, and insurgents.

Myanmar’s internal instability has further complicated the security landscape.

Abandoned arms and ammunition from the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) have reportedly fallen into the hands of the Arakan Army. There is credible concern that armed groups in the CHT may be involved in trafficking these weapons. Some tribal individuals are believed to have received combat training from Myanmar’s Chin National Front and the Arakan Army, and have allegedly participated in direct combat operations in Rakhine.

The spread of narco-terrorism from Myanmar has affected not only the CHT but also other parts of Bangladesh. Meanwhile, evangelization efforts by certain international NGOs continue to influence the region’s sociopolitical dynamics. In the absence of active engagement by national political parties, regional groups have militarized their operations, disrupting civilian life and undermining governance.

Human rights violations—including murder, abduction, rape, extortion, land grabbing, and incitement of communal violence—are alarmingly frequent. Women and children are particularly vulnerable. Recent reports suggest that armed groups are coercing women into participating in rallies and public gatherings under threat of fines and intimidation. Students from ethnic minority communities are being prevented from attending school under similar pressures.

This situation demands a unified and strategic response. Bangladesh must reject separatist agendas and reinforce its security infrastructure in the CHT. Equitable development must be prioritized to ensure that all communities—tribal and Bengali alike—benefit from the region’s vast potential. Every citizen must be free to practice their faith, culture, and traditions without fear or coercion.

We must pursue parallel progress in state-building and nation-building, ensuring guaranteed social and political rights for all residents. Greater participation of ethnic minorities in national political parties is essential. Border security must be strengthened, and anti-state activities conducted from neighboring territories—such as those linked to individuals like Karunalankar Bhante (alias Monogit Jumma), former vice president of JSS—must be decisively addressed.

Let us come together to build a peaceful, prosperous, and harmonious Chittagong Hill Tracts—one that reflects the unity, resilience, and inclusive spirit of Bangladesh.